Interest rates are frequently cited in financial news, yet their fundamental role as the “price tag on money” is often underestimated. For retail investors and consumers alike, the fluctuation of these rates is arguably the single most significant driver of financial health, influencing everything from mortgage affordability to portfolio valuations. It moves the conversation from simply “picking stocks” to understanding the macroeconomic tides that raise or lower all ships. By monitoring interest rate trends, investors can better position their portfolios to mitigate risk and capitalize on the shifting cost of money.

This article examines the mechanisms through which interest rates shape the economy and provides a structural analysis of their impact on retail investment portfolios.

The Mechanism: How Central Banks Steer the Economy

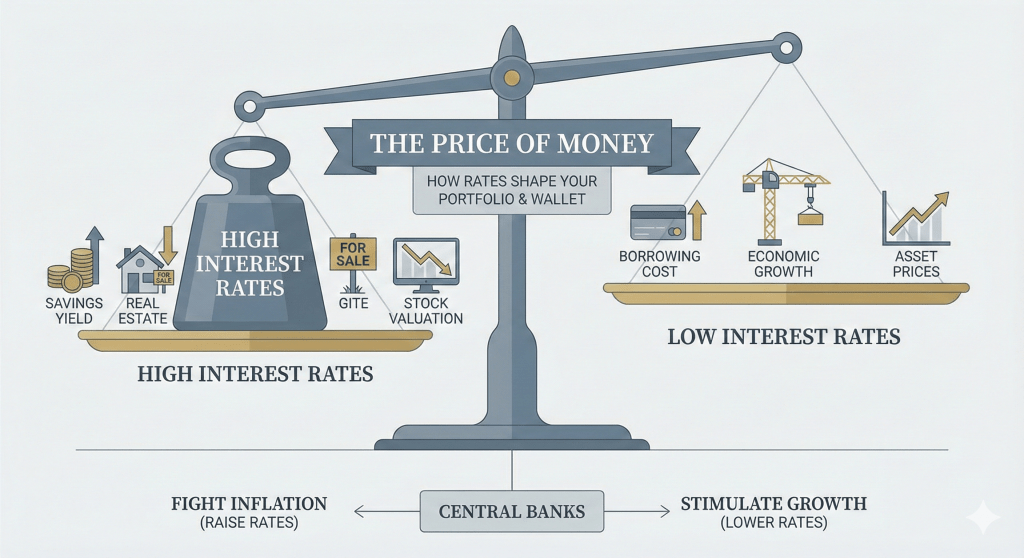

Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States or the Bank of England in the United Kingdom or Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in India, utilize interest rates as their primary lever to manage economic stability. The core objective is typically to balance inflation against economic growth.

- Combating Inflation: When an economy “overheats”—characterized by rapidly rising prices—central banks raise the benchmark interest rate. This increases the cost of borrowing for commercial banks, a cost that is subsequently passed down to businesses and consumers. The intent is to cool spending and stabilize prices.

- Stimulating Growth: Conversely, during economic downturns, central banks lower rates to make borrowing cheaper. This liquidity encourages businesses to invest in expansion and consumers to spend, effectively “jump-starting” the economy.

The Direct Impact on Personal Finances

Before analyzing investment portfolios, it is crucial to understand the immediate effects on personal capital, often referred to as “The Wallet Effect.”

1. The Cost of Debt

In a high-interest-rate environment, the cost of servicing variable-rate debt increases. This is most visible in:

- Mortgages: Higher rates significantly increase monthly payments for new buyers and those on variable-rate mortgages, often cooling housing demand.

- Consumer Credit: Credit card annual percentage rates (APRs) and auto loans rise, reducing disposable income.

2. The Incentive to Save

Conversely, rising rates benefit savers. High-Yield Savings Accounts (HYSAs) and Certificates of Deposit (CDs) offer competitive risk-free returns, incentivizing capital preservation over spending.

The Impact on Retail Investment Portfolios

When the “risk-free” rate of return offered by government bonds rises, it fundamentally alters the valuation logic for all other asset classes.

1. Equities (Stocks)

The relationship between interest rates and stock prices is generally inverse.

- Valuation Compression: Professional analysts value companies based on the present value of their future cash flows. When interest rates rise, the “discount rate” applied to these future earnings increases, making them worth less in today’s dollars.

- Growth vs. Value: This dynamic disproportionately affects Growth Stocks (such as technology firms), whose valuations rely heavily on earnings projected far into the future. Value Stocks, which typically generate strong current cash flows, tend to be more resilient.

- Corporate Costs: Higher rates increase borrowing costs for corporations, potentially squeezing profit margins and depressing share prices.

2. Fixed Income (Bonds)

The bond market adheres to a strict mathematical rule: bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions.

- The Seesaw Effect: If an investor holds a bond yielding 3% and market rates rise to 5%, the existing bond becomes less valuable because new bonds are now issued with the higher yield. The price of the older bond must drop to compensate.

- Duration Risk: Investors holding individual bonds to maturity are largely insulated from these price swings. However, investors holding Bond ETFs will see the Net Asset Value (NAV) of their funds decline during periods of rising rates.

3. Real Estate and REITs

Real estate is highly sensitive to the cost of capital.

- Direct Ownership: As mortgage rates rise, purchasing power declines. This often forces sellers to lower prices to attract buyers, leading to a stagnation or drop in property values.

- REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts): REITs compete with bonds for investor capital. When risk-free government bonds offer high yields (e.g., 5%), the appeal of a risky REIT yielding 4% diminishes, typically leading to a sell-off in the sector.

Conclusion: The Risk-Free Rate as a Benchmark

Ultimately, interest rates set the “hurdle rate” for all investments. The yield on a government Treasury bond is considered the Risk-Free Rate.

- If the risk-free rate is 1%, a stock offering a volatile 7% return appears highly attractive.

- If the risk-free rate rises to 5%, the same stock offering 7% becomes less compelling, as the investor is assuming significant equity risk for only a 2% premium (spread).